For nearly two decades we have been told that ‘partnership’ is the way forward, bringing us all together in ‘one big happy family’. But is partnership working really a confidence trick, confirming and exploiting unequal power relationships? Here Professor Jonathan Davies of De Montfort University outlines the arguments and trails his recent book which locates the fashion for partnership working right in the heart of the global neo-liberal project.

For nearly two decades we have been told that ‘partnership’ is the way forward, bringing us all together in ‘one big happy family’. But is partnership working really a confidence trick, confirming and exploiting unequal power relationships? Here Professor Jonathan Davies of De Montfort University outlines the arguments and trails his recent book which locates the fashion for partnership working right in the heart of the global neo-liberal project.

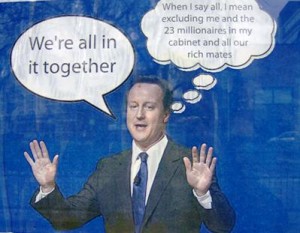

This, we are told, is an era of ‘partnership’ requiring government, business and voluntary and community organisations to cooperate for the common good. Partnership is the solution to everything from poverty and political disengagement to crime-fighting, economic development and environmental protection. If anything the ‘big society’ demands yet more partnership, with communities exhorted to run public services and plug the gap left by cuts. The zeitgeist is reflected in E. M. Forster’s epigraph to Howard’s End: ‘Only Connect’.

Collaboration is nothing new. Government and voluntary organisations have always cooperated because community work relies on grants and, increasingly, contracts. What makes the last 20 years different is the explosion of partnerships: bodies like New Deal for Communities and Local Strategic Partnerships, on which community activists sit as co-decision makers. New Labour considered citizen involvement in these bodies vital for local democratic renewal and empowerment. Many community groups welcomed the partnership ‘big tent’ in 1997, after 18 years of Tory government.

There is an enormous body of academic work reflecting on the experience of community in partnership in the UK and internationally. Some of the evidence is undoubtedly positive, but there is a pervasive sense that instead of empowering communities, partnerships were often tokenistic, manipulative and even exclusionary. The ‘control-freakery’ of public officials is one problem: when citizens raise awkward demands, they are often ignored and sometimes branded ‘trouble-makers’ by managers, themselves under intense pressure to meet targets. The difference in life-experiences between community activists and senior public officials is another challenge, making meaningful communication difficult. Some academics argue that partnerships try more-or-less subtly to change the behaviour and attitudes of community representatives. Others point to the experience of frustration at tokenistic forms of engagement. In short, partnerships appear not to have delivered much by way of community empowerment, if by this we mean an authentic and effective political voice. As a community organisation in London put it, ‘networking’ is ‘not-working’.

This perspective poses some difficult questions. Why did partnerships not live up to the promise? And what should campaigning community groups do about it? My book ‘Challenging Governance Theory: From Networks to Hegemony’ addresses the first question and touches on the second. Karl Marx saw the entanglement of the state with civil society as one of the most striking features of capitalism. He wrote: “The centralized state machinery … entoils (inmeshes) the living civil society like a boa constrictor”. He therefore saw the liberal goal of separating state, market and civil society into autonomous realms as utopian, unrealistic.

Marx’s insights were further developed by the Italian revolutionary Antonio Gramsci in his theories of ‘hegemony’ and the ‘integral state’. The ruling class uses the state apparatus to try and cultivate ‘hegemony’, meaning widespread assent for its ideas and activities in society as a whole. The more successful it is, the more the state can use a light touch and govern at a distance. However, Like Marx, Gramsci recognized that capitalist societies are inherently unstable and conflict-prone. Consequently, capitalism needs a strong state. Hegemony is difficult to maintain and however sincerely liberals might want to roll the state back, they cannot do it. Slashing public services does not mean it simply disappears; rather, it becomes more authoritarian. Markets have to be regulated and contracts enforced. The iniquitous and polarizing outcomes of economic competition have to be managed too. Government has to intervene to maintain social stability and order. Pickets and rioters have to be policed and imprisoned. The Occupy protestors have to be removed. The mortgage companies must be paid, defaulters evicted.

Gramsci’s concept of the integral state explains how states are compelled to apply both ‘consensual’ and ‘coercive’ governing techniques and thus why the separation of state, market and civil society was always a liberal pipe-dream. These are quite abstract ideas, but they can help explain why partnerships seem more effective at controlling and manipulating communities than in giving them an authentic political voice. Free market fundamentalists may think what they like, but the state cannot give up these disciplinary functions. Moreover, swingeing cuts are bringing the coercive ‘strong state’ to the fore and further undermining the prospects of an authentic partnership with communities.

But, if this is right, what are the implications for community groups? Should they quit partnerships or continue to participate and do their best to influence decisions? This is obviously not a simple choice. Those organizations seeking government grants and contracts, or representing vulnerable client groups, are reluctant to exit dialogue with public officials because this might appear inherently self-defeating. Yet, there is considerable evidence that pressures and compromises arising from gross power inequalities undermine the autonomy of voluntary groups in these relationships. The way some partnerships co-opt community groups into decisions about where the axe should fall is a glaring example. The option of rejecting public spending cuts altogether is never allowed onto the agenda.

And, what about the position of campaigning organisations, which see their aim as organizing and representing disadvantaged groups and fighting for social justice? The barriers to achieving this through partnership were always formidable under New Labour and appear insurmountable in the age of crisis and austerity. It would be foolish and presumptuous for an ivory tower academic to say ‘never join partnerships’, but the prospects for resisting cuts and defending communities through these mechanisms seem bleak. In this context, campaigning community groups may have little option but to engage in dissident, outright opposition and insurgency. Organizations like NCIA and NATCAN are doing excellent work in this area. The Arab Spring, the European revolt against austerity, the Occupy Wall Street movement and mass strikes in defence of pensions burst onto the scene in 2011, showcasing the potential for forceful resistance. If they are to make meaningful gains in 2012, independent community groups will be at the heart of these struggles and many others.

Challenging Governance Theory: From Networks to Hegemony, by Jonathan S Davies, was published by The Policy Press in September 2011. http://www.policypress.co.uk/display.asp?ISB=9781847426147.

Jonathan S Davies

Professor of Critical Policy Studies

De Montfort University