We hear a lot from service providers about how they have no alternative but bend to government and state policies or risk going out of business. But another way is possible. Those of us who went to the recent NCIA meeting in Sheffield were lucky enough to hear Gina Clayton talk about the work of ASSIST, of which she is Chair. ASSIST is a local project that – in direct contradiction of official Home Office policy – supports destitute refused asylum seekers, with accommodation, cash, bus passes and a range of advice and social support. And does this through the support of good Sheffield people and without dependence on state cash. Here we reproduce her inspiring talk…

We hear a lot from service providers about how they have no alternative but bend to government and state policies or risk going out of business. But another way is possible. Those of us who went to the recent NCIA meeting in Sheffield were lucky enough to hear Gina Clayton talk about the work of ASSIST, of which she is Chair. ASSIST is a local project that – in direct contradiction of official Home Office policy – supports destitute refused asylum seekers, with accommodation, cash, bus passes and a range of advice and social support. And does this through the support of good Sheffield people and without dependence on state cash. Here we reproduce her inspiring talk…

“Lesley Pollard, the Sheffield organiser of this event, has given me these questions to address:

- What does your organisation do?

- What are your organisation’s aims?

- How you personally and as an organisation have faced the kinds of difficulties highlighted in the NCIA work.

- How have you overcome them – or not.

- What is your bottom line – what the dilemmas have been for you when balancing your independence to advocate, represent and empower the people you work with vs relationships with statutory agencies.

I’ll try to do this in 15 minutes!

What do we do?

Simply – we support destitute refused asylum seekers, with accommodation, cash, bus passes and a range of advice and social support. When people are refused asylum in the UK, those who do not have children are made destitute. That means that once all their appeal rights are finished, they are evicted from the accommodation which was provided by the Home Office, and they have no money at all to live on. They are not entitled to housing even though they are homeless, nor welfare benefits, nor secondary health care. They are not allowed to work. They are completely destitute.

Questioner: why are they not removed from the country?

That’s a good question. Why not? Firstly, let me say that although they have been refused asylum, this was not necessarily the right decision. There are many problems in the asylum system and some people who are refused asylum are still afraid for the same reasons that made them flee in the first place. Secondly, the Home Office has great difficulty in removing people. It is an expensive process. Often the governments of home countries do not cooperate to provide travel documents, or the asylum seeker may be unable to fulfil their requirements for evidence of e.g. their birthplace to enable documents to be provided, or there may be no safe route of return, and so on. Sometimes the Home Office is inefficient. But – whatever the reason – whether the person themselves is still afraid to go or not, and whether they cooperate or not, government policy is that they are now destitute – sleeping on the street – with nothing. Officially they are expected to be destitute, and part of the reason for this is that the government – or some part of it – believes that if life is unpleasant enough people will choose to return to their home country. This is all part of the policy which generated the Home Office ‘Hostile Environment Working Group.’ You’ll have heard of that, as Sarah Teather exposed it – a government working group set up to share ideas on how to ‘deny the benefits of the UK’ to those who have no immigration permission to be here – or can’t prove they have. This is a wide group of people. We can’t talk about all the reasons today why people are in this position. There are many. But one is that they are a refused asylum seeker – though they may well be a refused asylum seeker who is still trying to find a way to show that they do have a legitimate asylum claim.

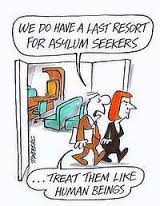

So – this is the ‘hostile environment’ – closely related to what is now called ‘the compliance environment’. Into this steps ASSIST – doing exactly what this policy does not want to happen. People of Sheffield got together and said that they could not sit by and see people starve on the streets. What are our aims? To ensure that people have a roof at night, have food to eat. I would also say – to embody respect for this group of people whom the government says can starve on the streets.

What difficulties have we faced especially in relation to independence and freedom to dissent?

Funding of course could be a problem. We are not going to get government funding. With one exception we have never had it. But then we don’t expect it. This is not really a problem. We give asylum seekers £20 cash per week, or less if they choose to have a bus pass. Many people find a bus pass even more useful than cash since they can go anywhere in South Yorkshire, get to their appointments, keep up relationships with friends, and get on a bus when it’s raining and they have nowhere else to go in the day. So – where do we get that cash? Obviously it’s not going to come from government. It comes from you, the people of Sheffield. The people of Sheffield give us money so that we can give it to asylum seekers. In one way it’s quite simple. ASSIST is based on solidarity, and we have wonderful public support. Government policy may be destitution, but the people say something different. We can be a channel for the voice that says ‘I stand by you.’ We are supported in many, many ways by the people of Sheffield, not only money. Time and goodwill are also vital to our existence and to the support we give.

Questioner: You have over 200 volunteers?

We do. People want to help. This morning I was with our accommodation worker, visiting a house which we bought last year with money given to us outright. Someone who knows of our work, and who knew we needed a house for destitute women asylum seekers, gave us the money to buy a house for this purpose. Just gave it – because she wanted to do that. We put this together with money from other kind donors, and we bought two houses last year. We have different kinds of accommodation – some asylum seekers are hosted in people’s homes. Some in rooms that we pay for in houses run by other organisations, and we have a house that has been lent to us for a long time. But last year for the first time we bought our own houses, and this is because people want to help. They decide in their own way how they want to do this and they do it. Sheffield is interesting because it has both wealth and poverty. What you can do depends on where you are, and we are lucky in Sheffield because of the particular political and social mix we have. But to return to this morning – I was visiting the house with another person who wants to buy a house and lend it to us! So people who have something are sharing it, through ASSIST, with people who have no home. This is solidarity in action. It is completely outside Home Office policy.

We do have grants, and we have to apply for grants for our existence. We have three part-time and two full-time workers and a lot of outgoings on the houses. Our budget now is over £200,000 p.a. But key to our independence is the solidarity and support of many people. And this gives us some freedom to act. This is also democracy.

We did have an interesting moment when G4S got the contract for housing and transport for asylum seekers in this area. They were desperate to improve their reputation. They had money. We thought about it. If we approached them for funding, it would be in their interests to respond, and anything we might ask for – to fund an accommodation project for instance – would be chicken feed for them. But we thought about how our clients would feel. We might be able, in fact, to receive money from G4S completely free of strings. They might be smart enough to know that would be a good way to give it. But even so, G4S employees have been responsible for terrible treatment of individuals, even including killing a person. How would our clients feel if we took money from G4S? Might we lose the most precious and irreplaceable asset that we have, which is trust? We didn’t approach them. It was a time of temptation but we’re through it now!

What other challenges? Are we under threat, since we act in a way that contradicts this particular Home Office policy? What about our very existence? Might we be made illegal? Well perhaps. But we are not alone. There are 27 other organisations in different parts of the country that are working in a similar way to us. We are a registered charity approved by the Charity Commission, as are all these organisations. We have eminent patrons. We take care to show that elements of ‘the establishment’ are with us. Some people may not like this tactic, but for the protection of our clients I think it’s important. For instance some political patrons are controversial figures, but I think that having Nick Clegg as our patron has been helpful to us. He has listened, because his constituents are our supporters. If there are moves to make us illegal, make no mistake there will be a right royal battle, and there will be a great deal on our side.

Challenges to our ethos – this is important. Over time, as destitution becomes an entrenched long term problem, and as we learn more, we want to do our best for our clients. Last year we did a survey of our clients to find out what they wanted from us. People do want more help with progressing their situation. We have been looking at how we can improve the help we give. Then the language we have discussed here today of ‘service delivery’ enters in. We are not delivering statutory services of course, so it’s different, but we need to be very alert to what we bring in along with our desires to improve the quality of what we give. I am all for improving quality. The asylum seekers we work with have had a raw deal – let us give them a good deal. There is no reason to ask them to ‘scrape by’. Let us give the best we can. However, in doing that, it is vital that we do not lose sight of our basic ethos of solidarity. We can learn from the statutory services, but, with respect to those colleagues, we will be selective about our learning.

In terms of relationship with the statutory services, as Lesley asked, we have not come under the pressures that people have described here today, but we are at an interesting moment. We have just for the first time made an approach to the City Council, based on case studies of what actually happens to a vulnerable person who is made destitute. We have received a very strong and welcoming response from the Cohesion, Migration and Integration Strategic Group. We are approaching the Council as confident colleagues who have something to offer in a difficult situation. We are not approaching as petitioners. We are pleased that they have responded in the way that they have. Our individual clients who qualify for support under the Care Act – a very small minority of our clients, through physical or mental illness have care needs which qualify them for this support – need help from the Council, and we will do our best to ensure that they receive it. But as an organisation we do not need anything from the Council other than to work together. This freedom we hope will enable us to enter into an appropriate relationship.

Relationship with the Home Office…..I believe in dialogue. That is a basic belief for me. But in recent experiences I am learning that this is not always possible. Outside ASSIST I have had some positive experience, but I’ll leave that there as time is running out. Dialogue with the Home Office, from where we stand, is difficult, though I like to keep hope alive.

Sharing premises – we have considered it. That may come in the future but one reason we have not done this when it has arisen in the past has been the need to keep our independence from any pressure to not do what we do.

To sum up – we are fortunate that our raison d’etre is based on dissent. Dissent from a policy that endorses destitution. We are also fortunate that our history is one of solidarity and that this remains fundamental to our way of working. These two grounds of our existence give us a firm foundation for independent action. Thank you.